How Willie Nelson Sees America

Written by admin on December 22, 2025

When Willie Nelson performs in and around New York, he parks his bus in Weehawken, New Jersey. While the band sleeps at a hotel in midtown Manhattan, he stays on board, playing dominoes, napping. Nelson keeps musician’s hours. For exercise, he does sit-ups, arm rolls, and leg lifts. He jogs in place. “I’m in pretty good shape, physically, for ninety-two,” he told me recently. “Woke up again this morning, so that’s good.”

On September 12th, Nelson drove down to the Freedom Mortgage Pavilion, in Camden. His band, a four-piece, was dressed all in black; Nelson wore black boots, black jeans, and a Bobby Bare T-shirt. His hair, which is thicker and darker than it appears under stage lights, hung in two braids to his waist. A scrim masked the front of the stage, and he walked out unseen, holding a straw cowboy hat. Annie, his wife of thirty-four years, rubbed his back and shoulders. A few friends watched from the wings: members of Sheryl Crow’s band, which had opened for him, and John Doe, the old punk musician, who had flown in from Austin. (At the next show, in Holmdel, Bruce Springsteen showed up.) Out front, big screens played the video for Nelson’s 1986 single “Living in the Promiseland.”

“Promiseland” joined Nelson’s preshow in the spring, after ICE ramped up its raids on immigrants. The lyrics speak on behalf of newcomers: “Give us your tired and weak / And we will make them strong / Bring us your foreign songs / And we will sing along.” The video cuts between footage of Holocaust survivors arriving on Liberty ships and of Haitian migrants on wooden boats. In Camden—two nights after the assassination of Charlie Kirk, one night after the State Department warned immigrants against “praising” his murder, hours after bomb threats forced the temporary closure of seven historically Black colleges—the images hit hard. When the video ended, three things happened at once: stagehands yanked the scrim away, Nelson sang the first notes of “Whiskey River,” and a giant American flag unfurled behind him.

“Whiskey River” has been Nelson’s opener for decades. He tends to start it with a loud, ringing G chord, struck nine times, like a bell. On this night, he sat out the beginning and took the first solo instead, strumming forcefully, pushing the tempo. “I don’t know what I’m going to do when I pick up a guitar,” Nelson said. He plays to find out, discovering new ways into songs he’s been singing, in some cases, since he was a child. “Willie loves to play music more than anyone I’ve ever met,” the musician Norah Jones told me. “He can’t stop, and he shouldn’t.” For Nelson, music is medicine—he won’t do the lung exercises his doctors prescribe, but “singing for an hour is good for you,” he says. His daughter Amy put it more bluntly: “I think it’s literally keeping him alive.”

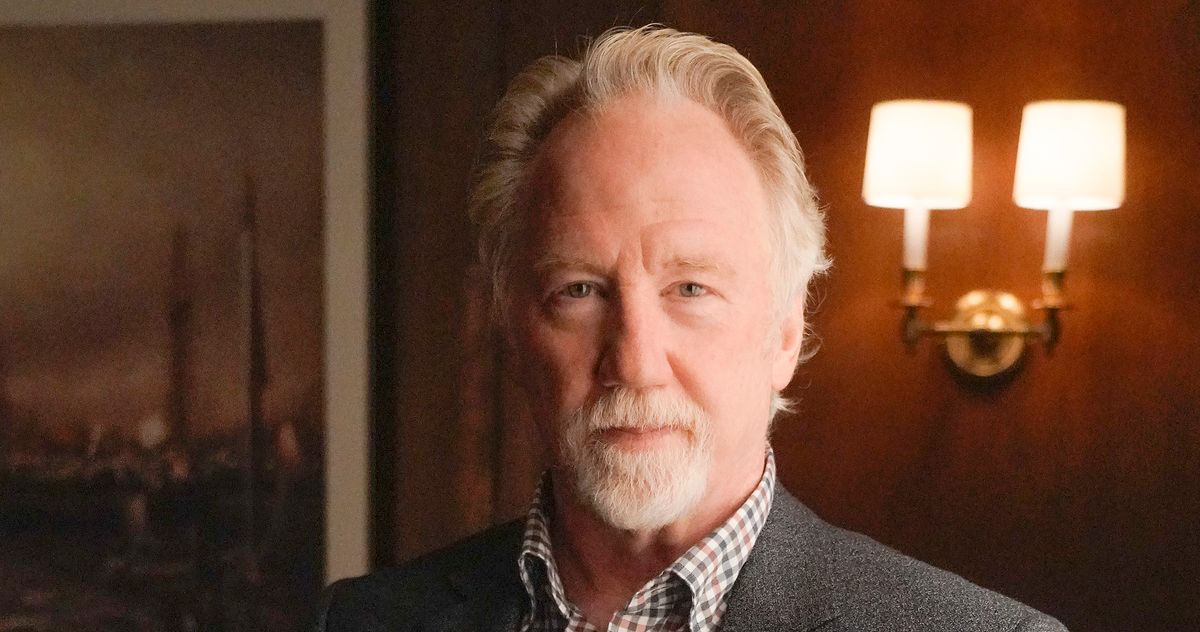

When one of Nelson’s tour buses needs to be replaced, he has the interior carefully re-created in the next one.Photograph by Danny Clinch

Last year, Nelson didn’t make it to every performance. On those nights, his older son, Lukas, filled in. At the end of the tour, no one knew if Nelson would go out again; five months later, he did. I started following him in February, in Florida. In Key West, Lukas and Annie flanked Nelson as he sat and rested before going on. Annie had her hand on the small of his back and Lukas on his shoulder; they looked like two cornermen coaxing a boxer back into the ring. Nelson suffers from emphysema. He barely survived COVID-19. (He got so sick he wanted to die; Annie told him if he did she would kill him.) His voice is still inky, he struggles for air, but he stays in charge, or lets go, as the moment requires.

“I’m definitely following Willie,” Nelson’s harmonica player, Mickey Raphael, told me. “He sets the tempo. He picks the songs.” Raphael is tall, with dark, curly hair and the easy swagger of a man who has spent his life onstage. When he started with Nelson, in 1973, there was no set list. Every night was “stream of consciousness,” catch-as-catch-can. Now, even with set lists taped to the carpet, Nelson might switch songs or skip ahead, lose his way, or drop verses—things he did as a younger man, too. At the end of a number that’s really careened, he’ll look over his shoulder and cross his arms in an umpire’s safe sign. “We made it,” he’s telling Raphael on these occasions. “We’re home.”

Nelson’s sense of home is elastic. For a long time, it was wherever work took him. In the fifties, when he was a young husband and father, in Texas, he washed dishes, trimmed trees, pumped gas, tooled saddles; he sold Bibles, Singer sewing machines, and Kirby vacuum cleaners door to door and drifted through a string of small-station radio jobs in Pleasanton, Denton, and Fort Worth. He was working as a d.j. at KVAN in Vancouver, Washington, when Mae Boren Axton, who co-wrote “Heartbreak Hotel,” came by the studio. Nelson played her a tape of his songs. She told him to seek his fortune in Nashville or back in Texas, where he ended up teaching guitar out of Mel Bay books, staying one lesson ahead of his students and writing extraordinary songs—“Crazy,” “Night Life,” “Funny How Time Slips Away”—that he offered to other artists for ten dollars apiece. Nelson’s oldest child, Lana, told me that when she found out he’d been peddling his songs she was crushed. “Nobody will ever know that you wrote them,” she said, “and how does that help?” “Look,” Nelson told her. “We got groceries.”

Larry Butler led the Sunset Playboys, a band at the Esquire Ballroom, in Houston. He told Nelson that his songs were worth a lot more, lent him fifty dollars, and hired him to play in the group. Others made similar offers—Nelson never forgot them—but there were songs, including “Night Life,” that he had to sell anyway. Twelve times a year, when the rent was due, the family moved. Lana said it never bothered her: “It’s not like you had developed this huge friendship with anybody over that thirty days.”

The idea of home comes up again and again in the songs Nelson wrote during this period, starting with “Misery Mansion,” recorded in 1960 as a rejoinder to “Heartbreak Hotel.” He followed that with “Where My House Lives,” “Lonely Little Mansion,” and “Home Motel”—a “crumbling last resort . . . on Lost Love Avenue.” In “Hello Walls,” Nelson pushes the metaphor to its limit, greeting not just the walls but the ceiling and the windows: “Is that a teardrop in the corner of your pane? / Now don’t you try to tell me that it’s rain.” The suffering in these songs is almost comical, but the hurt under the wordplay was real. Faron Young’s 1961 recording of “Hello Walls” became Nelson’s first No. 1 hit in Nashville, where he spent the sixties, until he finally grew to suspect that, for him, home might not be any one place at all.

“That’s his living room,” Nelson’s lighting director, Budrock Prewitt, told me on the road to Camden. He meant the stage—specifically, a twelve-by-thirty-two-foot maroon rug that Nelson’s crew rolls out at each venue before putting every instrument, amp, and monitor in the same spot as always. Whenever Nelson needs to replace the bus, a company that he’s been working with for decades re-creates the same interior in the next one, as precisely as possible. And Nelson keeps his buses leased year-round, whether they’re in use or not. “They park up and wait for us to come back,” his production manager, Alex Blagg, told me. “My bunk is my bunk.”

Nelson’s band does not have its own name. On ticket stubs and marquees, they’re simply Family, as in “Willie Nelson and Family.” For fifty years, Nelson’s sister Bobbie anchored the group from behind a grand piano. She and Willie had a pact: they’d play to the end of the road. When Nelson’s drummer, Paul English, died, he was replaced by his brother, Billy. Jody Payne was Nelson’s longtime guitar player; now his son Waylon plays in the band. Bee Spears started on bass at nineteen and stayed until his death, at sixty-two. Mickey Raphael, who joined the band at twenty-one, is now seventy-four.

Nelson’s road crew is family, too. His tour manager, John Selman, is the son of Wally Selman, who ran the Texas Opry House; he was hired twenty years ago, straight out of college. Prewitt and Larry Gorham, a Hells Angel who handles security, have been with Nelson since the seventies. So has Nelson’s manager, Mark Rothbaum. Rothbaum’s parents fled Poland in 1937; his mother died when he was thirteen. He stopped caring about school. “I was just fucking angry,” Rothbaum told me. He got a job with a business manager in Manhattan. One day, he saw Nelson behind a glass partition at his office, on West Fifty-seventh Street. “He looked like Jesus Christ,” Rothbaum recalled. “He was glowing.” Rothbaum worked his way into the circle. “I adopted them. But I had to do it. I had to become useful.” He and Nelson have never had a contract. “You couldn’t put a piece of paper between us,” he says.

Family members call this Willie World, and it, too, is elastic. When the steel player Jimmy Day drank his way out of it, Nelson didn’t replace him. The steel parts simply disappeared. When Spears went on tour with Guy Clark, Nelson brought in Chris Ethridge, of the Flying Burrito Brothers, to play bass—and, when Spears called and asked to come home, Nelson welcomed him back and kept Ethridge on. For a while, he toured with two bassists and two drummers: a full-tilt-boogie band captured on “Willie and Family Live,” from 1978. At around the same time, Leon Russell joined them on piano, bringing along his saxophone player and the great Nigerian percussionist Ambrose Campbell. When Grady Martin, the top session player in Nashville, retired from studio recording, he went on the road, too, upping the number of people onstage to eleven. “Willie ran a refugee camp, to some extent,” Steve Earle told me.

Bee Spears died in 2011, Jody Payne in 2013, Paul English in 2020, and Bobbie Nelson in 2022. “The biggest change was Sister Bobbie,” Kevin Smith, who now plays bass, told me. Bobbie outlined the chord structure of every song. After her death, Smith was shocked at how little sound there was onstage. These days, Nelson and Raphael take all the solos. Sets are shorter. Lukas sits in when he’s not out touring on his own; his brother Micah, who plays guitar with Neil Young, joins when he can. But Nelson’s sound has been stripped to its essence. “It’s more like spoken word now,” Raphael said. “Like poetry with a rhythm section.”

Nelson goes from number to number with almost no patter—an approach he learned from the great Texas bandleader Bob Wills, who kept audiences on the dance floor for hours. In Camden, he got through twenty-four songs in sixty-five minutes, pausing only to wipe his brow with a washcloth or to sip from a Willie’s Remedy mug full of warm tea. The set didn’t feel hurried—on “Funny How Time Slips Away,” Nelson gave the song’s ironies and regrets space to sink in—but the crew kept an eye on the clock. After Camden and Holmdel, Nelson was scheduled to play Maryland, Indiana, Wisconsin, and, finally, Farm Aid, at the University of Minnesota: six shows in eight days at the end of eight months on the road. “He just keeps going and going,” Annie said. “He’s Benjamin Buttoning me.”

I ran into Annie in Camden, doing her laundry backstage by the catering station. She and Nelson met in the eighties, on the set of a remake of “Stagecoach.” Annie is two decades younger than Willie. She is sharp, protective, and unflappable, with a wide smile and long, curly hair that she has allowed to go gray. She told me that the build-out for Farm Aid was supposed to have started that day in Minneapolis. CNN was planning a live telecast. But Teamsters Local 320—made up of custodians, groundskeepers, and food-service workers at the university—had chosen that moment to go on strike. Members of IATSE, the stagehands’ union, would not cross the picket line, and neither would Nelson. Cancelling the concert, though, would break faith with the people Farm Aid was meant to serve. “It’s not great for us,” Annie said. “But who really suffers? The farmers. This year of all years.”

Farm Aid was supposed to have been a one-off. Nelson started it with Neil Young and John Mellencamp in 1985, after decades of touring the Farm Belt and watching small farms disappear—in the eighties, they were going under at a rate of one every thirty minutes. Rising interest rates, falling land values, export embargoes, and drought left farmers unable to make payments on loans they’d taken out, often at the urging of the federal government. Farm Aid was meant to send money their way and force the rest of the country to pay attention. The first show, in Champaign, Illinois, raised nine million dollars, drew seventy thousand people, and gave family farmers a national stage and an organization that could help as loans came due and the banks moved in. Nelson signed every grant check by hand; he still does. Farm debt is back near its peak in the eighties—higher, by some measures—and rural suicide rates have climbed sharply. “The tariffs are killing farmers,” Annie said, “including small family farmers, who get killed the worst.” When those farms go under, she said, “the acre traders and hedge funds and J. D. Vance’s billionaire buddies” swoop in. “Then we get ‘Soylent Green.’ ”

Nelson has stripped his sound down to its essence. “Like poetry with a rhythm section,” his harmonica player said.Photograph by Peter Fisher for The New Yorker

For Nelson, this is not an adopted cause. His parents and grandparents left Arkansas for Abbott, Texas, in 1929, part of an early-Depression push of Southern farm families into the Blackland Prairie—a stretch of dark, rich soil through the center of the state. Nelson dragged a long sack with a strap across his body through cotton fields when he was small enough to pick bolls from the stalk without bending. “Tried to get as much as you could, because they’d pay you by the pound,” Nelson recalled. “He was literally a child laborer,” Amy Nelson told me. Before that, “his grandparents staked him out in the fields so that they could work.”

Nelson’s grandparents, Alfred and Nancy, took him and Bobbie in after their parents split up. Bobbie was two; Willie was six months old. Willie remembers them studying music together, by correspondence course, in the light of a kerosene lamp. They bought Bobbie a piano—she took to it right away—and, when Willie was six, Alfred ordered a Stella guitar from the Sears catalogue. A few months later, Alfred caught pneumonia and died. County authorities came by after his passing, threatening to put the children into foster care; Willie and Bobbie ran and hid in a ditch until they left. Nancy went out to work in the fields and took a job in a school cafeteria, exhausting herself to hold on to the children. At night, they made a ritual out of braiding her hair.

Nelson went on to join the Future Farmers of America. He planted lettuce and turnips in the family garden, raised hogs, and borrowed horses to ride. In high school, he pole-vaulted and played baseball, basketball, and football. He didn’t talk much—Bobbie was more outgoing—but they were both popular. Poor by conventional standards, but no more than the people around them.

I passed through Abbott a few times during the months I followed Nelson around. The barbershop where he shined shoes and sang for quarters is gone, along with Abbott’s drugstores, groceries, banks, and boarding houses. The Methodist church Nelson attended is still there—he pays for its upkeep. So is the Baptist church across the street. The population, roughly three hundred and fifty, is about what it was when Nelson was born. But the town, low and flat under a wide, empty sky, is quieter now. When Nelson was growing up, an interurban train line ran down to Waco. Six miles over, in the town of West, the Czechs had their fraternal-society halls, where they drank beer and danced waltzes, schottisches, and polkas. A Mexican family lived across the street from the Nelsons—their corridos drifted over—and newly arrived Southern families brought string instruments and shape-note hymnals. In the cotton rows, Willie and Bobbie heard work songs and blues. “I learned a lot of music just being out in the fields,” Nelson recalled. A blacksmith named John Rejcek had sixteen children and a family band that played in West; by the age of ten, Willie was sitting in with his guitar, inaudible under the tubas but earning eight dollars a night, several times what the cotton fields paid. He heard Sinatra and the Grand Ole Opry on the family Philco once electricity came in. Sounds filtered in from so many directions, Nelson became a kind of crossroads himself.

“Willie means more to me than the Liberty Bell,” Jeff Tweedy told me. Tweedy and his band, Wilco, played a few dates with Nelson this year, as part of the annual Outlaw Music Festival, which Nelson headlined along with Bob Dylan. (Other performers included Billy Strings and Lucinda Williams.) Tweedy said he admires Nelson’s vision of America—“a big tent, and it should be”—and the way Nelson says what he thinks without rancor, always punching up. “He doesn’t aim at his fellow-citizens. He aims at corporations. He aims at injustice.”

Nelson has a knack for leaning left without losing the room. He stumped for Jimmy Carter, who was a friend, and for the former congressman and Presidential candidate Dennis Kucinich; he co-chairs the advisory board of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws; he has pushed for the use of biofuels, running his tour buses on vegetable oil and soybeans; he opposed the war in Iraq. In 2006, he recorded a Ned Sublette song called “Cowboys Are Frequently, Secretly Fond of Each Other.” “I’ve known straight and gay people all my life,” he told Texas Monthly. “I can’t tell the difference. People are people where I came from.” (“Beer for My Horses,” a hang-’em-high duet with Toby Keith, has aged less well.)

In 2018, when the government began separating families at the southern border, Nelson said, “Christians everywhere should be up in arms.” That fall, he played a new song, “Vote ’Em Out,” at a rally for Beto O’Rourke, who was running for Senate. O’Rourke told me the point wasn’t only the stand Nelson took; it was the idea of Texas he represented. There was a temptation, O’Rourke said, to accept the caricature of Texas as “extreme, conservative, macho, tough-guy,” though for people like him, who’d lived there all their lives, “true Texas is kindness, hospitality, open hearts.” Nelson, he said, embodied “the best of Texas: you can be a freak, a weirdo, a cowboy, a rancher, a cello player, whatever. He’s the patron saint of that—growing his hair, rejecting corporate music, and just being a good fucking human being.”

At Nelson’s concerts, all of those types gather. They always have. In the seventies, when Nelson was still playing dance halls, ranch hands and refinery workers shared the floor with hippies who’d heard his songs on FM radio. It was a volatile mix. At the Half-Dollar, outside Houston, groups of long-haired kids sat in front of the stage as cowboys two-stepped behind them. The cowboys “would start dancing, do a little spin, and kick somebody in the back,” Steve Earle recalled. “Willie caught it out of the corner of his eye.” Nelson stopped the band in the middle of a song. “There’s room for some to sit and for some to dance,” he said, and, as soon as he did so, there was.

“People out there get to clap their hands and sing for a couple hours, and then they go home feeling better,” Nelson said. “I get the same enjoyment that they do—it’s an equal exchange of energy.” As a young man in Texas, Nelson taught Sunday school and considered the ministry. On the bus in Weehawken, I asked if he saw his work as akin to a preacher’s. “Oh, I don’t know about that,” Nelson said. “I don’t try to preach to nobody.” Annie disagreed: “I think he’s a shaman.” Musicians like him draw strangers together, she said. “Let’s face it, we’re being divided intentionally. That’s part of the playbook—divide and conquer. It’s been around a long time. When somebody’s saying hello to somebody without knowing their political ideology, and they’re just enjoying music together, that’s church. That’s healing. That’s really important right now. Really, really important.”

In June and July, I caught a leg of Nelson’s tour that stretched from Franklin, Tennessee, to the Woodlands, in Texas: Nashville to Houston, almost a road map of his working life. Nelson arrived in Nashville at 3 a.m. on June 23rd, four hours after a show in Cincinnati. Later that day, his bus pulled up at East Iris Studios, in Berry Hill, a low-slung village just south of downtown. With his producer, Buddy Cannon, behind the mixing board, Nelson sang ten songs in four hours, most of an album he’ll release in the spring. A record of Rodney Crowell songs, “Oh What a Beautiful World,” had come out in April; “Workin’ Man: Willie Sings Merle” was slated for November. Once, in the eighties, Nelson recorded four albums in a single day. But a session like this one still felt like a solid day’s work.

Cannon, a soft-spoken seventy-eight-year-old with glasses and a neat white mustache, first saw Nelson in the late sixties, at a small club on Chicago’s North Side. He went on to play bass in Mel Tillis’s band, then wrote for George Strait and produced for Kenny Chesney. He and Nelson started working together in 2008. At the time, Nelson’s albums were leaning toward standards and covers. One day, Cannon woke up to a series of texts—lines of new lyrics, followed by a question: “What do you think?” Cannon sent a few lines in response, and Nelson replied, “Put a melody to it and send it back to me.” Proceeding in that fashion, they wrote “Roll Me Up and Smoke Me When I Die,” a song that Nelson still plays in concert. In all, they’ve written more than fifty songs and made more than a dozen albums together, including the so-called mortality trilogy: “God’s Problem Child,” “Last Man Standing,” and “Ride Me Back Home.”

Nelson arrived in Nashville in 1960 and was hired to write for the publishing company Pamper Music.Photograph from Michael Ochs Archives / Getty

Nelson doesn’t mind doing two or three takes of a number. He bristles at four. Don Was, who produced Nelson’s album “Across the Borderline,” in 1992, told me about recording the title track in Dublin, where Nelson had a night off from touring. They spent an hour working out the arrangement—talking, not playing—then went for the first take. Halfway through the second verse, Was thought, Oh, man, this is unbelievable. Please, nobody fuck up. “He plays this incredible solo in the middle. Third verse, I’m really freaking out—please, nobody. And nobody did.” Kris Kristofferson added harmonies; that was the only overdub. Then Nelson rolled a joint and marked it with a Sharpie, about three-quarters of the way down. He told the house engineer, “I’m going to smoke this joint. When it gets burned down to the blue dot, your mix is done.” Forty-five minutes later, it was. “That’s the mix on the album,” Was said.

These days, Cannon cuts backing tracks with musicians who “get Willie and don’t look at the clock.” Nelson comes in later, as he was doing now, to play and sing. “He has no pitch issues,” Cannon says. “He’s allergic to out-of-tune-ness.” But Nelson plays odd tricks with rhythm—phrasing behind the beat while his guitar rushes forward. “Willie’s timing is so weird,” Raphael told me. “It’s like a snake slithering across the ground.” Nelson is one of the most imitated guitarists in the world, Cannon says, but, without his feel, imitators “sound silly.” When Nelson plays, “even the crazy shit sounds beautiful.” Cannon tries not to sand down the edges: “I love his music too much to screw it up.”

Nelson got to Nashville in 1960 and scrambled until he was hired to write for Pamper Music, a publishing company. Pamper was home to the strongest writers in town; even so, Nelson stood out. His songs were complicated—they had more chords than your average cowboy song—but catchy, with a psychological depth that recalled Method acting as much as traditional country storytelling. “Hello Walls” and “Crazy” took listeners inside minds turned against themselves. “Funny How Time Slips Away” is more conversational—the narrator seems to be catching up with an old flame—until we realize that he’s talking to himself. For him, time has not passed at all.

Rodney Crowell sets Nelson’s writing next to Hank Williams’s. Williams, he told me, “had it all to himself, that simplicity and that straight-ahead English language”—a plainspoken line like “I can’t help it if I’m still in love with you.” Working with the same tools, Nelson arrived somewhere else: “a different way of painting.” Stranger images, more irony, a sensibility that doesn’t report feeling so much as worry it. “Let’s just say what it is,” Crowell says. “He was a poet.”

Nelson doesn’t love playing these sad, early songs. Writing them took too much out of him, and singing them pulls him back to where he was when they were written. Since the seventies, he’s corralled them into a medley, gotten them out of the way all at once. But they were the songs that made him. Billy Walker recorded “Funny How Time Slips Away” in 1961. A few months later, Patsy Cline recorded “Crazy.” Ray Price recorded “Night Life” in 1963—it became his opening number—and hired Nelson to play in his band. Nelson by then was a top-tier songwriter, making six figures in royalties, sometimes flying between tour dates while Price and the rest of his band rode the bus. He divorced his first wife, Martha Matthews—they’d wed as teen-agers—and married the country singer Shirley Collie, then blew that marriage up, too. “I was that cowboy,” he told the novelist Bud Shrake. “Going home with somebody different every night,” drinking a bottle of whiskey and smoking two or three packs of cigarettes a day. “I thought that was what I had to do. It’s the way Hank Williams done it.” In that world, he said, “you’re supposed to die at the right time.”

Nelson kept trying to make it as a performer. His own band, which came to be called the Offenders (later the Record Men), played dance halls and opened for bigger acts. But even in Texas, where he developed a loyal following, Nelson was not a top draw. He gave up on the road at the age of thirty and bought a small farm in Ridgetop, outside Nashville. He raised hogs and kept horses. A sheep named Pamper wandered in and out of the house. A sign on the mailbox read “Willie Nelson & Many Others.”

A few days before Christmas, 1970, the house at Ridgetop caught fire. Nelson rushed home and ran inside for his guitar and a case full of weed while the house burned around him. He left Tennessee and settled on a ranch in Texas near Bandera, in the Hill Country. His daughter Lana, who by now had children of her own, recalls flying to Austin to visit Nelson and failing to recognize him until her son shouted, “That’s Grandpa!” The last time she’d seen him, in Nashville, he had short hair and wore country-club clothes. Now he had long hair and a beard and wore a T-shirt, a bandanna, and an earring. “He went from jazz musician to hippie,” she said.

In Texas, Nelson cut back on the drinking. His face thinned out. His features sharpened. He ran five miles a day through the Hill Country, practiced martial arts, kept smoking weed—it tamped the rage down, he said—and read spiritual tracts and “The Power of Positive Thinking.” People who killed the mood didn’t stay in his orbit for long. “Somewhere along the way, I realized that you have to imagine what you want and then get out of the way and let it happen,” he told me. The strategy worked. Within a few years, Nelson was famous. Within a few more, he’d become an icon. “I couldn’t believe I was sitting there swapping songs with him,” Cannon said of their first meeting.

“He went from jazz musician to hippie,” Lana Nelson said of her father (with Waylon Jennings, in 1974).Photograph by Melinda Wickman Swearingen / the Wittliff Collections at Texas State University

Cannon was back behind the board when Nelson returned to East Iris Studios, on our second day in Nashville. He wore a checkered shirt, a baseball cap, and a KN95 face mask. (The COVID protocols around Nelson are strict; Annie wears masks, too, when they’re out in public.) Printouts of songs for an upcoming Christmas album were scattered across the console. Raphael watched from a couch set against the back wall; Mark Rothbaum sat next to him. Nelson sat in a straight-backed chair on the other side of the glass, hair in a ponytail, hands in his lap. A track came in over the speakers. He started to sing. When he wanted to project, he leaned back from the microphone the way singers did before engineers rode the levels. Nelson does not have the buttery baritone of a Ray Price or a Waylon Jennings; in the sixties, he was a woodwind stuck in the brass section. Over time, he developed a richer tone and a warm vibrato, which is now mostly gone. But his voice is still warm and reedy—a deviated septum helps give it that slight nasal edge—and the notes land precisely, if not predictably. “What age takes in speed and strength,” Rothbaum said, “he gains in anticipation.”

Nelson knocked the album’s remaining songs down, one after the other, in one or two takes. After the last—about a town called Uncertain, Texas, where nobody can make up their mind—Cannon hit the talk-back button. “If I’m not mistaken, we’re finished,” he said. “All right!” Nelson replied. “Let’s go get drunk.”

Nashville sells itself as the buckle of the Bible Belt. Memphis is a river town, a capital of the Delta. Nelson’s bus pulled in on June 27th, a Friday. The air was thicker here, the heat heavier. I found Mickey Raphael in the catering tent, picking at a plate of barbecue. “We played Memphis the night Elvis died,” he said. “Jerry Lee Lewis climbed up onstage, drunk as fuck, and said, ‘I’m the King now.’ ” Lewis tried to sit down next to Bobbie at the piano. His bodyguard flashed a gun. From behind the drum kit, Paul English flashed his, and order was restored. “Paul’s reputation was you just didn’t fuck with him,” Raphael said.

English was Nelson’s tour manager, protector, and best friend, as well as his drummer. He was six feet tall and wiry, with sharp cheekbones, a goatee, and long, pointy sideburns; he looked like the Devil and leaned into it, wearing capes lined with red satin, settling with promoters by laying a pistol on the table while keeping another tucked in his boot. “Willie was very trusting,” Raphael said. “Paul, not so much.” English grew up on the north side of Fort Worth, running with a group called the Peroxide Gang. In his twenties, he pimped girls out of down-and-outs—cheap motels along Jacksboro Highway. Nelson memorialized their friendship in a song, “Me and Paul,” a tally of missed flights, shakedowns, and busted shows. “He was used to getting Willie out of any kind of trouble,” Raphael said. “He was watching all the time.”

The Family was still swapping stories about Paul the next day, when they crossed the state line into Missouri. They played outside St. Louis that night, then headed for Branson, driving past a micro-emporium, “America’s #1 Patriotic Superstore”—selling MAGA hats, MAGA socks, MAGA Teddy bears, MAGA magnets—and the Uranus Fudge Factory, which sold air fresheners and “fudge from Uranus.” Everyone who’d been with Nelson for a long time had terrible associations with this part of the country, dating back thirty-some years. “Don’t ask me about Branson,” Raphael said. “I’ve blocked it out.” The trouble began in 1990, when the I.R.S. came after Nelson for more than sixteen million dollars in back taxes. On the day after he’d come home to Texas from a tour, federal agents seized everything: his ranch and recording studio, instruments, sound equipment, gold records. Friends and farmers paid him back for all the favors he’d done. They showed up with cashier’s checks at auctions, buying back land and possessions and holding it all for him in trust, even as late-night hosts turned Nelson’s woes into a running joke—one about the hillbilly who’d got above his station. At Nelson’s shows, audiences threw tens and twenties onstage.

Nelson’s politics are progressive—he stumped for Jimmy Carter, a close friend—but he has a knack for leaning left without losing the room.Photograph by Rick Diamond / Getty

Nelson sued his accounting firm, Price Waterhouse, for pushing bad tax shelters—the company settled—and released a double album to square the rest of the debt. He sold “The I.R.S. Tapes: Who’ll Buy My Memories?” through a late-night 1-800 number. The recordings, twenty-four of his best songs in a little more than an hour, were just his voice and guitar, Nelson at his most intimate and unguarded. Most of the proceeds went straight to the U.S. Treasury.

Six months later, on Christmas Day, 1991, Nelson’s oldest son, Billy, who was thirty-three, took his life in a cabin at Ridgetop. Nelson buried him next to his own grandparents in the family plot near Abbott. “It’s not something you get over,” he’s said. “It’s something you get through.” He stayed off the road for a while, then signed on for a long run in Branson, playing two shows a day, six days a week, for tour groups and convention crowds. It kept the Family working but pinned them in place. In “Me and Paul,” Nelson had sung, “I guess Nashville was the roughest.” After six months in Missouri, he changed the lyric to “Branson.”

Thunder Ridge, the venue Nelson was playing next, sits eleven miles outside Branson, on a limestone bluff above Table Rock Lake. Fans lined up for beer and T-shirts—“Willie for President,” “Have a Willie Nice Day!”—and bottles of Willie’s Remedy, a THC-infused tonic that promises euphoria without the hangover. From the lawn, you could see clear into Arkansas. In the afternoon, the sky above the amphitheatre darkened. A gray funnel cloud dropped down. The crowd out front took shelter; backstage, everyone ran for the buses, but the production manager’s girlfriend at the time, Lindsey Seidl, who had driven down from Wichita with her father, stayed outside, sitting on the tailgate of a pickup with Kansas plates. One by one, musicians and roadies stepped back off the buses and joined them. “How worried should we be?” someone asked.

Seidl grew up watching storms cross flat country. This, she explained, was a cold-air funnel. The main cell had blown past the ridge. Now warm air trapped in the valley was pulling the cold clouds down into a spiral that looked worse than it was. “That’s not the one you need to worry about,” she said, then pointed at a darker wall of weather behind it. “That one is.” We climbed back on the bus. Larry Gorham leaned over and mentioned that he’d been with Nelson for forty-seven years. “Do you know how many shows we’ve missed because of the weather?” he said. “Not many.”

The first storm passed over. The second one hit—straight-line winds—and passed over us, too. When the winds died down, Raphael pulled out a black raincoat and walked to the stage. Each band’s gear had been set up on dollies and risers, secured under forty-foot-long tents. Nelson’s tent was stage left, all the way in the back. It alone had collapsed. A maroon drum lay on its side. Water dripped from the sagging canvas and pooled on the floor. Annie, in her summer uniform—a knee-length skirt, a T-shirt, and Keds—joined the crew, pulling equipment out of the puddles. Raphael snatched his harmonica case and an old Southwestern blanket—“one thing that hasn’t gotten lost” along the way, he said.

The Branson show didn’t happen. Neither did the next show, outside Oklahoma City. At the convention center there, the crew spread its stuff out to dry. Bobby Lemons, the soundman, bent over a big analog board with a hair dryer, one of a dozen that the crew had bought at a nearby Walmart, along with a leaf blower and tubs of DampRid. Large pieces of fabric—scrims, a banner, and Nelson’s American flag—lay flat under fluorescent lights.

Nelson did make the next date, a Fourth of July show in Austin. Heavy rains had come through the night before. Two hours west of the city, in the Hill Country, long stretches of highway vanished under brown water. At a girls’ camp in Kerr County, floodwater tore cabins from their foundations and carried them down the Guadalupe River. Austin cancelled its fireworks show. The full scale of the damage wasn’t clear yet, but by the time Nelson played Houston, on the sixth, it had come into focus: eighty-two people dead, at least forty-one still missing. Pat Green, a musician who had mentored Waylon Payne, lost four family members in the floods: his younger brother, his brother’s wife, and two of the couple’s children. Payne got the news backstage—first the numbers, then the names.

The Family had been out on this leg of the tour for seventeen days; after Houston, they’d be off for two weeks. Raphael would be flying home to Nashville. The rest of the band would be staying in Texas. Waylon Payne was already planning the drive down to his tiny town in the Hill Country, where flooding had cracked the foundation of his house in half. As soon as he got back, he said, he planned to cook fifty pounds of meat and make tacos for the first responders. “If we go out next year,” Raphael said, “we’ll need an ark.”

That night in the Woodlands, north of Houston, the “Promiseland” video played, the flag dropped, Nelson cruised through the Nashville medley. Payne sang “Help Me Make It Through the Night,” a Kris Kristofferson ballad that had given Payne’s mother, Sammi Smith, a No. 1 country hit and a Grammy in 1971, and also “Workin’ Man Blues,” which Jody Payne used to sing with the Family. As the set drew to a close, Raphael picked up a button accordion he plays on “Last Leaf,” Nelson’s cover of a song by Tom Waits. “The autumn took the rest / But it won’t take me,” Nelson sang.

Since the seventies, Nelson has ended his shows with a gospel medley. At first, it was “Amazing Grace,” followed by “Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” “Uncloudy Day,” and “I Saw the Light.” “I’ll Fly Away” drifted in during the eighties, with no discussion or planning. Nelson still sings it. In Houston, members of the Avett Brothers and the Mavericks, bands that had opened for Nelson, came out to join him. Raphael handed his accordion to Percy Cardona, who plays with the Mavericks. He was wearing a burgundy vest and mariachi pants, cowboy boots, and a bolo tie. “I’m Mexican American, but I love country music, too,” he told me later. “I try to mix the two.” The band started playing. During “I Saw the Light,” Nelson stood, threw his cowboy hat into the crowd, blew a kiss, and walked off. The band played on for a moment, then followed, and Cardona stayed, accordion strapped to his chest, the last man on the stage.

Guitars dry out as they age, becoming lighter and more resonant. Playing them speeds the process along. Nelson got Trigger, a nylon-stringed Martin, in 1969. Since then, he has hardly played anything else. “When Trigger goes, I’ll quit,” he’s said, though musicians who study him closely point to his touch, not the instrument. “You can hear the sound of his voice in what he’s playing,” Bill Frisell told me. “If I gave him one of my guitars, it would sound like Willie Nelson. It wouldn’t sound like me.”

Jazz musicians have always admired Nelson. He doesn’t seem to be afraid of anything, Frisell said. Most players panic when there’s space, he explained; they feel they have to fill it. But Willie? “He’s cool.” The critic Ben Ratliff describes Nelson’s singing as “the kind of fast that’s so fast it’s laconic,” and notes that, if one tries to sing along, “it’s impossible to hit the microsecond that he begins the phrase” or to guess “what he’s going to do with the phrase—the weird way he’ll scoop a phrase melodically, and then end up not exactly on the note but just a shade under it sometimes.” When I asked Sonny Rollins about Nelson, he spelled the word “freedom” out, letter by letter. “Willie’s not doing it,” Rollins said. “He’s doing it.”

Nelson found that freedom in 1973, when he made “Shotgun Willie” for Atlantic, a New York label that was experimenting with country. He recorded the album—his sixteenth—in Manhattan, with Atlantic’s session players, members of the Nashville A-Team, and, for the first time, his road band: Paul English, Bee Spears, and Bobbie. He wrote most of the songs, selected the others—including his first recording of “Whiskey River”—and played Trigger throughout.

“Shotgun Willie” is the first Nelson album I fell in love with. I’d heard some of his stark Nashville demos in college—they’d floored me—but “Shotgun Willie” threw me for a loop. The beat on some songs sat so far back, it sounded like it was calling, long distance, from a Wilson Pickett session. (Nelson’s producers, Arif Mardin and Jerry Wexler, had worked with Pickett, too.) Donny Hathaway wrote the string charts; the Memphis Horns played on the title track. Country radio didn’t know where to put it, and it didn’t sell, but “Shotgun Willie” gave Nelson a sound closer to what he heard in his head, and material that he still plays.

For the follow-up, “Phases and Stages,” Wexler took him to Muscle Shoals, in Alabama, to work with the rhythm section that had backed Pickett and Aretha Franklin. The album, which Nelson recorded in two days, told a divorce story, twice: side one from the wife’s point of view, side two from the husband’s. It sold about as well as the previous record. Atlantic shuttered its Nashville office soon afterward. Bleak as the album is, it has an emotional sophistication that Nelson’s early songs lacked, with narrators working their way through the wreckage rather than wallowing: “After carefully considerin’ the whole situation / I stand with my back to the wall / Walkin’ is better than runnin’ away / And crawlin’ ain’t no good at all.” Texas Monthly, which keeps a running list of Nelson’s albums—all hundred and fifty-five of them, ranked—puts “Phases and Stages,” a “perfect record,” at No. 1.

Nelson started Farm Aid with Neil Young and John Mellencamp in 1985, after touring the Farm Belt for decades and watching small farms disappear.Photograph by Larry Salzman / AP

Nelson kept swerving. He recorded his next album, “Red Headed Stranger,” for Columbia, in three days, at a studio outside Dallas. Label executives assumed that they were listening to demos and asked him when it would be finished. He said it was done. If worse came to worst, he figured, he could always spend six months of the year playing I-35 up into Canada and the next six months playing his way back down. Instead, the album’s first single, “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain,” became Nelson’s first No. 1, and the album sold millions. At forty-two, Nelson became a superstar—then veered again. On “Stardust,” he turned to standards, songs that he’d played at dance halls since he was a kid: “Georgia on My Mind,” “September Song,” “Blue Skies.”

The move wasn’t as odd as it looked. For years, Nelson had been writing thirty-two-bar AABA songs in disguise. “Stardust” made the lineage obvious while slyly sounding more modern than its song list suggests. The title track opens with a contrapuntal figure—rising melody, descending bass—that could almost be “Stairway to Heaven.” “Blue Skies” starts with a disco-like pulse. Nelson and the album’s producer, Booker T. Jones, loved Hoagy Carmichael’s tunes and met on that common ground, with Jones handling the arrangements. Jones pushed the songs into his own harmonic world, putting “Georgia on My Mind” in D-flat—an unusual key for a guitarist, with five flats. Jones learned the flat keys from studying Russian composers, he told me, and writing for Albert King. “Those are special keys for emotional exercises,” he said. “Deep, deep, serious grooves.”

Jones gave Nelson room to roam, to show off. But there was “big time” pushback on the album, he said. “It wasn’t just new for Columbia. It was new for Nashville. It was new for the time. It was somewhat out of the question.” Inside Columbia’s Nashville operation, he recalled, people could hear how good the material sounded; the question was how it was supposed to work—and how a Black producer was supposed to be standing at the center of a major-label country record. But Nelson’s contract gave him creative control, and Rothbaum made the machinery move. “They had no idea what to do with Willie,” Rothbaum told me. “He fit nothing they had ever encountered.” The album became Nelson’s biggest seller by far, spinning off two No. 1 singles (“Georgia” and “Blue Skies”), with “All of Me” reaching No. 3. Having already proved himself as a great American songwriter, Nelson now revealed himself as a great interpreter of the American Songbook—“a natural when it came to starting in the wrong place and ending up in the right place,” Jones said.

“You never know exactly what he’s going to do,” Micah Nelson told me, describing the concerts he’s played with his dad. He went on, “You’re always present. Nobody’s phoning it in, because you never know where the spirit’s going to take him.” Nelson may sing a verse way ahead of everyone, when they’re “still on the first chord,” and the instinct is to speed up, to catch him, Micah said. “It’s, like, No, no, he’s waiting for us over there, three blocks away.” Nelson lets the band close the gap, then keep going. “He’s singing so outside of the pocket, there is no pocket. He’s obliterating any sort of timing,” Micah continued. Somehow, it works. Any number of times, Micah has thought, Oh, shit, he’s lost the plot. He always finds it again. Playing with Nelson is like performing with the Flying Wallendas, Micah said, or with Neil Young’s band. It’s the opposite of perfectly choreographed shows with backing tracks that all but play themselves. There’s never a safety net. “Obviously, it helps to have great songs,” he added. “Now that I say it, the songs are the safety net. You really can’t go wrong when you have good songs.”

“Willie, Annie, and I are in the position of having to negotiate a labor dispute,” Mark Rothbaum told me on September 12th. “It’s not really what we do.” In Minneapolis, the Teamsters were still out on strike. Governor Tim Walz, who’d attended the second Farm Aid, in Austin, when he was a twenty-two-year-old mortgage clerk, got involved, along with Senator Amy Klobuchar. Walz told me that the concert came “within an hour or two” of being cancelled. “It would have been a shame on so many fronts,” he said. But, on September 13th, the university and the union reached a deal. The build-out started that day.

Nelson’s crew arrived in Minneapolis a week later. Just outside the stadium, a sprawl of tents and booths called Homegrown Village went up. Concertgoers swapped seeds and shared beekeeping tips while the bands played. Amanda Koehler, who runs an urban farm in St. Paul, described barriers facing young farmers—capital, credit, access to land. She took heart, she said, watching solidarity grow between laborers and farmworkers, citing Farm Aid’s refusal to cross the picket line as a small but important example. I ducked back inside just in time to see Lukas Nelson walk out onstage.

Lukas’s memories of Farm Aid go back to early childhood. He started on the guitar around age ten, after asking his father what he wanted for his birthday. “You should learn how to play guitar,” Nelson told him. “That would make me feel good.” He practiced for eight, sometimes ten, hours a day, becoming obsessed, Annie told me, “to the point that I had to take it from him at night.” Nelson told Lukas to work on his singing. “There’s a lot of great guitar players out there,” he said, “but no one has your voice.” When Lukas performed one of his own songs in public for the first time, it was at Farm Aid. By then, an extended family had grown up around the occasion, reconvening every fall. “It’s almost like Christmastime,” he told me.

This year, Lukas and Micah joined their father for a fifty-minute set that started with “Whiskey River” and ended at 1 A.M. with two dozen people onstage singing Hank Williams’s “I Saw the Light.” Nelson smiled and dropped his eyes as the song ended, then looked out at the audience. “Thank all y’all,” he said before he walked off, heading straight back to his bus while the band squeezed into a shuttle headed for the hotel.

There were songs, like “The Party’s Over,” that drifted in and out of Nelson’s set during the months I spent with him. There were constants, too, like “Angel Flying Too Close to the Ground.” The song, from the 1980 film “Honeysuckle Rose,” tells the story of a man who’s learned to love and let go, years removed from the embittered character who sang “Funny How Time Slips Away.” Each time I heard it, I thought of the way he’d rewritten his own narrative—letting the road pull him out of corners that used to close in—and what his travels cost him and those in his slipstream.

Amy recalled a time when she and her sister were trampled by fans trying to get to their father: “My mom said, ‘He’s not going to really know what that’s like, because they stop when they get to him. They will plow through you to get to him.’ ” Any hard feelings fell away when she thought about the alternative—years her father had spent going nowhere, the life he might have led had he not broken through. “Whatever resentment I had for his fans disappeared when I started looking at it from that perspective.”

There were powerful lessons, Lukas told me, in watching Nelson live his life’s purpose, rather than manage the expectations of those he was close to. “That’s a great way to live,” he said. “But it’s hard for people to understand, because most people require consistency, closeness, and physical proximity with their loved ones. I’ve learned how to not need that, which I’m grateful for.”

“Angel” is Lucinda Williams’s favorite Nelson song, and Chris Stapleton’s. Dylan recorded it during sessions for his album “Infidels,” in 1983, and found his own way in, turning the song’s rise and fall into a hymn, digging into its rhymes as if they were his own: “Leave me / If you need to / I will / Still remember / Angel / Flying too close to the ground.” I played the cover for Raphael, who hadn’t heard it. “He makes it sound like it’s his song,” Raphael said. I asked Dylan about Nelson, and he wrote back with a warning: “It’s hard to talk about Willie without saying something stupid or irrelevant, he is so much of everything.” He went on:

How can you make sense of him? How would you define the indefinable or the unfathomable? What is there to say? Ancient Viking Soul? Master Builder of the Impossible? Patron poet of people who never quite fit in and don’t much care to? Moonshine Philosopher? Tumbleweed singer with a PhD? Red Bandana troubadour, braids like twin ropes lassoing eternity? What do you say about a guy who plays an old, battered guitar that he treats like it’s the last loyal dog in the universe? Cowboy apparition, writes songs with holes that you can crawl through to escape from something. Voice like a warm porchlight left on for wanderers who kissed goodbye too soon or stayed too long. I guess you can say all that. But it really doesn’t tell you a lot or explain anything about Willie. Personally speaking I’ve always known him to be kind, generous, tolerant and understanding of human feebleness, a benefactor, a father and a friend. He’s like the invisible air. He’s high and low. He’s in harmony with nature. And that’s what makes him Willie.

In Camden, Nelson played “Angel” midway through his set. The crowd rose to its feet—they would stay that way, swaying and singing along, until the show came to its end. Bathed in reddish light that turned his hair and skin the color of copper, he let Trigger do much of the talking, using fewer notes than he would have ten years ago, or twenty, but saying more. I wondered if, among other things, Nelson was saying goodbye. Then he played “On the Road Again.” ♦